ection>

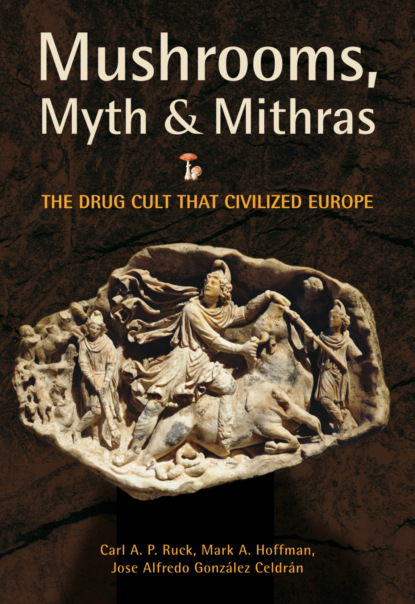

Mushrooms, Myth & Mithras

The Drug Cult that Civilized Europe

Carl A. P. Ruck

Mark A. Hoffman

José Alfredo González Celdrán

Copyright © 2011 by Carl A. P. Ruck, Mark Alwin Hoffman, José Alfredo González Celdrán

Images from M. J. Vermaseren, Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae, 1956, 2 volumes, are reproduced with the gracious permission of the publisher Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Cover photo by Andreas Praefcke. Mithras Relief (tauroctony) depicting Mithras killing a sacred bull, from Aquileia, second of 2nd century AD. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Inv. No. I 624.

Cover illustration by von Albin Schmalfuß, 1897. Fliegenpilz (Amanita muscaria).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ruck, Carl A. P.

Mushrooms, myth, and Mithras : the drug cult that civilized Europe /

Carl A. P. Ruck, Mark A. Hoffman, José Alfredo González Celdrán.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. 292) and index.

ISBN 978-0-87286-470-2 (alk. paper)

1. Mithraism. 2. Hallucinogenic drugs and religious experience. 3. Amanita muscaria—Religious aspects—Mithraism. I. Hoffman, Mark Alwin.

II. González Celdrán, José Alfredo, 1963–III. Title.

BL1585.R83 2009

299'.15—dc22

2008037005

City Lights Books are published at the City Lights Bookstore

261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133

Visit our website: www.citylights.com

Nothing is so great, nothing else is greater than the Bull that carries Heaven and Earth. Like a shaft he pierces through the Earth’s habitation and strews living beings as the Wind strews the clouds; decked out like Varuna and Mitra, he causes light to stream forth from the forest.

—Rig Veda 10.31

Prelude

The First Supper: Entheogens and the Origin of Religion

Our greatest blessings come to us by way of madness, provided madness is given us by way of divine gift.

—Socrates, Phaedrus

Various traditions recall the events of a “First Supper.” In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the story unfolds in a garden called Eden. In that version of the myth, a serpent persuades humans to eat the fruit of a sacred Tree of Knowledge, thus bringing man and God together. In the patriarchal reformation of Judaism, with its morbid dread of the power of the goddess, the story of the First Supper was revised. But even there, the jealous god observes that the food made humans more like Himself, endowed with knowledge of good and evil and the wisdom of the angels.

Such substances are now termed entheogens. Combining the ancient Greek adjective entheos (“inspired, animated with deity”) and the verbal root in genesis (“becoming”), it signifies “something that causes the divine to reside within one.” When used in rituals, entheogens can be seen as sacramental substances whose ingestion provides a communion and shared existence between the human and the divine. In the context of ceremony and ritual, the individual becomes “at one with God.”

Prior to the recent revival of interest in psychoactive plants and compounds, the need for a new word for these botanical mediators led psychiatrist Humphry Osmond to coin the term psychedelic, “to fathom Hell or soar angelic,” as he described it in a letter to Aldous Huxley. Within just a few years, however, conservative backlash against the 1960s counterculture had contaminated the word with the perception of criminality, recklessness, and abuse. The term was derived from the Greek words psyche, for the “human mind, soul or spirit,” and delos, “clear, manifest.” In fact, early experimentation with such substances in the modern West suggested similarity with psychotic states, as implied in the coinage of psychomimetic and psychotropic.

An entheogen is any substance that, when ingested, catalyzes or generates an altered state of consciousness that is deemed to have spiritual significance. Symbolic surrogates, lacking the appropriate chemistry of psychoactive plants and compounds, may induce a similar experience through cultural indoctrination and suggestion or personal subjectivity, and could also be termed entheogens. Like shamanism itself, entheogenic spirituality is dependent upon and defined by the states of consciousness experienced. In many cultures, accessing such states is considered culturally essential to the perpetuation of a society’s underlying natural and spiritual interconnection with the cosmos. Altered states of consciousness are very often considered in dispensable to such core shamanic practices as diagnosis of ailments, curing, soul retrieval, and communication with deceased ancestors.

In myth, transformations of consciousness are an integral element in the basic story of the hero or heroine who encounters pathways of communication between the human and an otherwise invisible realm, and such experiences are viewed as part of the ongoing renewal of the community’s spiritual well-being. These transformations even underlie the semishamanic philosophies of Gnosis in the ancient Classical world. Among other peoples, they ensure perpetual contact with the wisdom and benevolence of the spiritual worlds.

Generally speaking, however, the study of entheogens is a comparatively recent phenomenon, as is their recognition as a formative influence on the shaping of both shamanic and so-called developed cultures. It is now widely accepted among specialists that entheogens and the ethnopharmacology of their plant sources represent one of the most direct, powerful, reliable, and indeed ancient means of inducing “authentic” shamanic states of consciousness. Entheogens may, in fact, be the most reliable way of inducing a profound and sustained alteration of consciousness commonly associated with ecstatic, shamanic states. Hence they are at the heart of such dependable and repeatable ceremonies as initiation rituals and other religious Mysteries.

When entheogens are taken in the context of a society’s sacred shamanic ceremonies, the culture’s mythopoetic traditions are often relived and reinfused with profound immediacy and power, heightening their spiritual sense of connection.

Entheogenic epiphany is commonly described as a state in which people experience their individual distinctions dissolve in a mystical, consubstantial communion with a force of profound sacred meaning. This ecstatic experience is interpreted as a pure and primal consciousness and sometimes described as the direct contact with the unobscured root of being. Since shamanic spirituality is inherently practical, it ascribes the highest importance to the regular access to such transcendental states; this point of contact ensures the undisturbed continuation of natural cycles and helps perpetually maintain a society’s underlying sense of centeredness, equilibrium, and balance. From a shamanic perspective, ecstatic contact also protects against the potential dangers of unappeased or neglected gods or spirits. The entheogenic experience, though entirely strange, dissimilar, and inexplicable in mundane language, is often described as feeling more real and vibrant than ordinary consciousness.

Some of the plants used for shamanic rituals have yielded important medicines, for shamans are traditional healers, often called “wise ones.” Other substances open up pathways to otherwise unseen worlds, with the spirit of the plant as guide to repair the invisible imbalance that is the cause of disease and plague. The word medicine has cognates in all the Indo-European languages and is related to meditate and middle, implying