her. “You still haven’t told me what you know about my parents,” she said.

He swung back and froze, apparently riveted by the sight of her feeding Christophe. His voice sounded husky as he said, “Your father was Henry’s only son, Philippe de Valmont.”

She heard only one word. “Was?”

“He died in a waterskiing mishap soon after you were born. He never knew he had a daughter.”

“And my mother?”

“Her name is Juliet Coghlan.”

Sarah drew a sharp breath. “My father’s secretary?” Sarah had known the woman through her childhood, without suspecting that they could be mother and daughter. Suddenly she understood why Juliet had been so affectionate toward her, giving her small gifts and treats, and making time for her, no matter how busy she had been.

Sarah remembered visiting her father’s office to find him and his secretary in the midst of a blazing argument. Uncharacteristic tears had streamed down Juliet’s face as she stormed out of the inner office. She had come up short at the sight of the distressed seven-year-old, but had refused to tell her what was wrong. Now Sarah wondered if she had been the focus of the disagreement.

Juliet had left the next day. There had been no calls or letters since, and James McInnes had told Sarah he didn’t know where his former secretary had gone.

“Prince Philippe met Juliet when she was holidaying in Carramer. They fell in love and sought Prince Henry’s permission to marry,” Josquin said.

Christophe had drifted off to sleep and didn’t stir when Sarah tucked him into one arm. Feeling unusually self-conscious, she adjusted her clothing with the other. “I gather Prince Henry refused to give them his blessing.”

“He wanted his son to marry a Carramer woman of his choosing.”

“What happened?”

“Philippe told his father that he intended to renounce his title and follow Juliet to America. The love affair continued until she discovered what he meant to do. Evidently she didn’t want him giving up everything on her account, so she pretended that the affair was over. She expected Philippe to return to Carramer and resume his royal duties.”

This was her father, her real father. A man who had so loved her mother that he had been willing to give up everything for her. “Did he come back to Carramer?”

“For a time. He and Henry were barely on speaking terms, but Philippe did his duty to the letter, although everyone who knew him could see that his heart belonged elsewhere.”

“How did you know he’d fathered a child, if he didn’t?”

The prince reached into his pocket and withdrew a slim leather wallet. From it, he extracted a photograph that he handed to her. “Through this.”

The air fled from her lungs as she looked at the photograph. “It’s a picture of me.” A similar one had stood atop the piano of her adoptive home for as long as she could remember.

“Read what’s written on the back.”

Sarah turned the picture over. The handwriting was Juliet’s. “‘My darling, I thought I could do this alone, but I need you. Our daughter needs you. Tell me what I should do.’” It was signed, “‘Jay.’”

Sarah looked up at Josquin, feeling tears stain her cheeks. How could her real father have turned his back on such an appeal? “I thought you said Philippe didn’t know about me.”

Josquin took the photograph from her and returned it to his wallet. “He didn’t. The photograph was delivered to his office an hour after he left to go waterskiing with friends. After returning from America, he was frequently preoccupied, and that day his mind wasn’t on what he was doing. Another vessel ran him down. Philippe died on the way to the hospital. He never saw the photograph.”

“Surely someone contacted Juliet to tell her what had happened?”

“Philippe’s staff didn’t know who Jay was, and Prince Henry was unapproachable for months after the accident. I think he blamed himself for Philippe’s state of mind.”

“He was to blame,” she said hotly. “If he hadn’t hounded the lovers, they’d have married and lived happily together.” With her, she thought. Henry was responsible for destroying three lives including hers.

“Try not to think too harshly of your grandfather,” Josquin urged. “He’s from the old school, and believed he was doing what was best for the province.”

“Don’t call that horrible man my grandfather. From the sound of him, Christophe and I are better off not having anything to do with him.”

Josquin gave a tight smile. “From what I’ve heard about him, you sound a lot like Philippe.”

“I should probably take that as a compliment.”

She stood up and lifted Christophe against her shoulder. He gave a most unregal burp, then settled back to sleep again. He didn’t waken when she placed him in the beautiful antique crib and tucked a soft blanket around him. Her heart swelled with love as she looked down at him. She couldn’t imagine treating her son as heartlessly as Henry had treated Philippe.

“You still haven’t explained how I came to be adopted,” she said, turning back to Josquin.

“As far as we know, it was arranged privately through Juliet’s association with your father.”

Sarah couldn’t keep the bitterness out of her voice. “Illegally, you mean?”

“Probably. There is no official record of the adoption. We assume that when she didn’t hear from Philippe, Juliet decided that he didn’t want to acknowledge their child. She already had an invalid mother depending on her and couldn’t cope with more. Your father and mother wanted a baby but they were unable to have children of their own. When James McInnes found out what a struggle Juliet was having, he persuaded her that it would be kinder to you if she let him adopt you. As his employee, she was able to see you on an almost weekly basis.”

Sarah thought about the argument between Juliet and her father. “All would have been well as long as my mother hadn’t insisted that I be told who I was. She had a blazing row with my adoptive father. I’d say that was the reason. She left soon afterward. When I asked where she’d gone, I was told nobody knew.”

“We were not able to establish her whereabouts, either,” Josquin said. “I’m sorry.”

Bleakness gripped Sarah as she faced the possibility that her mother might have died. Now she would never know that Philippe hadn’t abandoned her, or Sarah herself. Her only consolation came from knowing that her real mother had tried to do her best for her daughter.

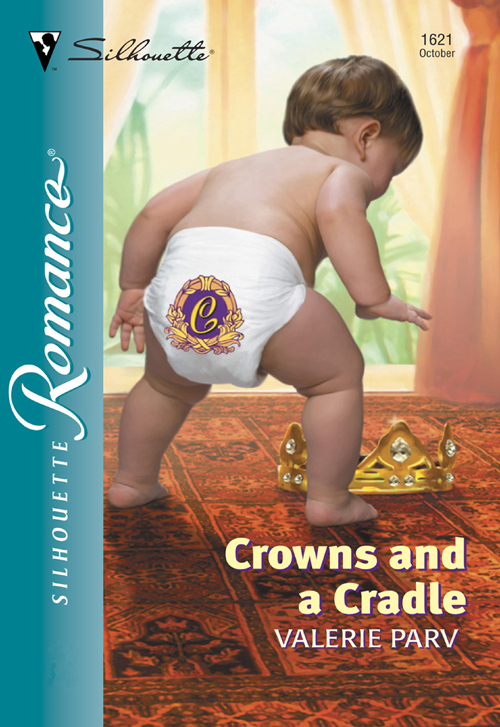

“You do realize what this means?” Josquin said. “Your son is not the only one of royal blood. You are in fact, Her Royal Highness, Princess Sarina de Valmont.”

Her knees jellied. “Every adopted child wonders if she’s really a princess.” Before he could respond, she added, “Does that make us cousins?”

He shook his head. “I’m from the de Marigny line.”

“Then how can Prince Henry of Valmont be your uncle?”

“It’s a courtesy title. He took over my education in my midteens when my parents proved less than adept at it.”

She didn’t miss the bitterness in his voice, and sensed that there was more to his admission, but he didn’t seem inclined to elaborate.

“Are you disappointed that we’re not related?” he asked.

She would have been more disappointed if they had been. She wasn’t sure why, because she had no romantic interest in him. If anything, she should despise him because of his loyalty to Prince Henry, the man who had destroyed her real family. “Why should I care either way?” she asked