have never in my life said, ‘Smack me, baby.’”

“And ‘tan my naughty ass!’”

I shoved him, laughing. “‘Tan my naughty ass?’”

“See! There you go again!” He ran his palms down my hips, took both my hands in one of his and rubbed my bottom with the other. “Just one?”

I bit my lip. “Okay. One.”

He gave my ass a wallop and his eyes lit up—meaning he was ready for business.

“Later,” I said. Because we’d agreed: never in the office. But I could still tease. I kissed his neck and wriggled as he ran his hands over me.

“You’ll play secretary tonight?” he asked, a bit breathlessly.

“Office manager.”

“Office manager it is,” he said, and spanked me again.

Rip was out all afternoon, so I had time to finish the ads before they were due. It was a near thing though, and I was halfway home before I realized I hadn’t stopped at Tazza Antiques. I wasn’t exactly bothered—if I forgot to buy the desiccated old pot, maybe Emily would agree to get something else. Something better. Like a magazine subscription.

I picked up my dog, Ny—a ridiculously red chow mix—and took him to the beach before going to my dad’s house. I stopped at Dad’s two or three times a week, to check in and mooch dinner. Actually, checking and mooching were one and the same. Because if he knew I was coming, he’d buy food. Otherwise, he’d eat cold cereal three times a day. He was a bit of an absentminded professor.

Ny romped with his dog buddies and chased seabirds through the waves until he was exhausted. I toweled him dry and helped him scramble into the cab of the pickup—he was getting chubby and needed an extra boost.

My truck was a silver Ford Ranger pickup, the Splash model with chrome wheels. I’d bought it with my Ask It Basket money—the only new vehicle I’d ever owned. If I closed my eyes and sniffed deeply, I could still smell the new-car perfume. Plus, it was half of the patented Anne Olsen System for Being Semi-Successful with Men. Step One: don’t care about long-term relationships. Men love this. They swarm. Step Two: drive a pickup. Women driving pickups are to men what men driving Armani suits are to women. Don’t ask me why.

Dad lived in the same old Victorian on the upper east side where I’d grown up. It was a mixed neighborhood, filled with old houses like my dad’s that locals had owned for thirty years, and the updated versions that wealthy L.A. people had recently bought and renovated.

Dad glanced up from his newspaper when I let myself in. “What’s hanging?”

“‘What’s hanging?’” I let Ny track his sandy paws inside and closed the door. “Where’d you hear that?”

“I like to keep up with you young people,” he said.

“I don’t know, Dad. I don’t feel so young anymore.”

“Of course.” He shook his newspaper derisively. “You’re bent with age at twenty-six.”

“Nine,” I said. “Twenty-nine.”

“Really?” he said. “That is old.”

“What?”

He laughed. You’d think after twenty-nine years, I’d know when he was teasing.

“Still gullible as a teenager,” he said. “Have you eaten?”

“Of course not.” I headed for the kitchen. “What’s for dinner?”

“Stuffed pork chops. You’re staying?”

“I am for pork chops.”

He followed me into the kitchen and checked the oven. Two pork chops and two potatoes were already baking.

“Why two?” I asked. “Am I stealing one of yours?”

“No,” he said, “I was making leftovers for tomorrow.”

I glanced upstairs. “You haven’t got a woman hiding in your bedroom, waiting for me to leave?”

“Of course not,” he said. “She’s in the bathroom.”

“Oh! Sorry! I should’ve called—” I saw his expression. “Ha-ha. Very funny.” I opened the fridge and grabbed a soda. “But the way you play the field, I keep expecting to hear you eloped.”

He shook his head. “Three girls is enough.”

“Why haven’t you remarried?” I wasn’t sure if I liked the idea, but my dad wasn’t really meant to live alone. “It’s been almost twenty years.”

“You’re one to talk, with all your boyfriends.” He grabbed lettuce and carrots for a salad. “You’re a female Lothario.”

“I am not.”

“You’re Lotharia.”

“I’m not Lotharia.”

“You break up with every man you date. I can’t imagine Rip’ll last much longer, poor guy.”

“You like him?” Every time Rip met my father, he tried to sell him a new house.

“The question is, do you?”

“He’s funny and smart and wonderful—what’s not to like?”

“You’re not getting VD?” Dad asked.

No, he didn’t mean VD VD. He meant Vague Dissatisfaction. I’d stupidly confessed to him once that I had an acute case of Vague Dissatisfaction. Nothing in particular was wrong, but nothing felt right. It was why I never stuck with things very long. Dad considered it a low-level social disease, which would flare up periodically into unsightly outbreaks: VD. Dad thought he was pretty funny.

I glared. “Everything’s fine. I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Then give me an onion.”

I gave him an onion, and we let the subject drop. He told university stories over dinner, and when we’d finished, he offered me Oreos for dessert.

“Is it a new package?” I asked.

“Anne, you’ve got to stop this.”

“My diet starts tomorrow.”

“You know what I mean. Your obsession with newness.”

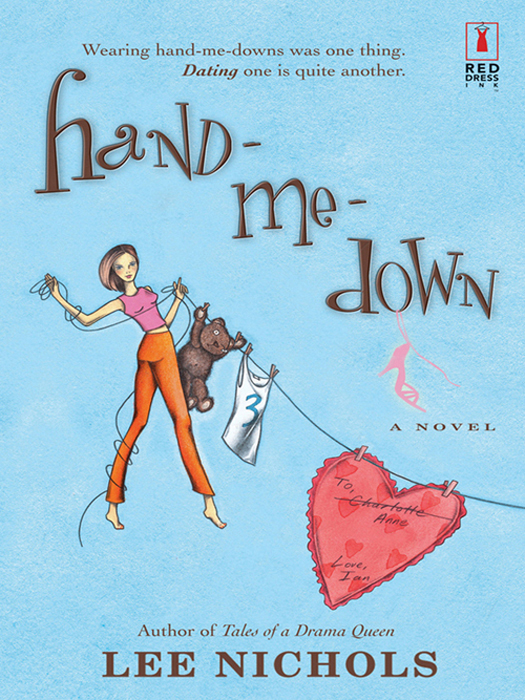

Easy for him to say. With two older sisters, hand-me-downs had been the primary fact of my young life.

Charlotte had a Malibu Barbie with a full wardrobe. Emily had a slightly used Malibu Barbie with two outfits. I had a one-armed, bald Barbie who enjoyed nudist colonies.

Charlotte wore Jordache when it was popular. Emily wore Jordache when it was passable. I wore Jordache when it was passé.

Charlotte learned to drive on a six-year-old VW Rabbit. Emily learned on a seven-year-old VW Rabbit. I learned on a twelve-year-old, rusted-out junker with suspicious stains on the seats and the faint odor of Gruyère.

But all I said to Dad was, “I don’t like stale Oreos is all.”

He lifted his pipe from the ashtray on the kitchen table and packed it with tobacco. “They’re fresh from the factory.”

“Where are they?” I asked, heading toward the pantry.

“Bottom shelf.”

I pulled the half-eaten package from the shelf and forced myself to take one. From the back. The very back. “Not bad.”

Dad looked pleased as he lit up his pipe, and I surreptitiously pulled a brand-new carton of milk from the fridge—ignoring the one which was already open—and poured myself a glass. I’d let him discover that little treat tomorrow.

When