James Whittaker and Nawang Gombu, and later Luther Jerstad and Barry Bishop, reached the summit by the South Col route; Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld successfully pioneered a new and difficult route on the West Ridge; and the scientific programmes brought back new insight into the nature of high-altitude glaciers and a wealth of information on man’s physiological machinery, his mental processes, and group behaviour.

The seed of the idea of challenging Everest by way of the West Ridge was planted by Dyhrenfurth early in the Expedition’s formative stage. It lay dormant until we were well on the road to the mountain, marching over the foothills of the Himalaya, before it grew into an unwavering dedication in the minds of Tom Hornbein, Willi Unsoeld, and their old climbing companions, Corbet, Emerson, and Breitenbach. Pioneering a new route on Everest excited everyone’s imagination, for a high reconnaissance of the Ridge would be a gratifying mountaineering achievement even though it fell short of the summit. But there is a vast gulf between success and the best of tries short of it. The Expedition would be a failure in nearly every sense if the whole of its effort had been expended in a courageous but unsuccessful attempt via the Ridge. The moral and contractual commitments we had accepted to make the Expedition possible made the decision clear. Until the summit was reached by the South Col—the surer way—no large-scale diversions, however attractive, should jeopardize this effort. The larger part of the team was no less dedicated to climbing Everest by the South Col than were others to exploring the West Ridge.

There was no doubt in our minds that following the ascent of Everest, the resources of the Expedition would be diverted to the West Ridge. The opportunity could not be passed over, for the Expedition possessed a rare asset: strong, skillful climbers who were totally dedicated to the task. Nevertheless, the patience of the West Ridgers would be tried in the weeks before May 1, when Whittaker and Gombu hoisted themselves and their flagpole onto the summit of Everest.

Inevitably the Expedition’s large size evoked the ancient but still favourite subject for debate among mountaineers: the merits of small versus large expeditions. The subject is heavily crusted with subjective values and consequently conducive to strong convictions, vigorous debate, and, of course, is impossible to spoil with definite conclusions. Climbers tend to be rugged individualists. To them climbing is not a sport in the true sense, least of all an organized sport. Rather, it is a deep personal experience enjoyed in its fullest only when shared with a few close companions. Large expeditions bring with them some of the trappings and restraints of organized society that the climber would just as soon leave behind.

Nevertheless, the large expeditions have, for the most part, offered the only opportunity to challenge the greatest Himalayan peaks with any reasonable expectation of success. No serious climber could resist the call to join such an expedition no matter how strong his feelings about its size and multiplicity of non-mountaineering commitments. If his convictions are strong, he cannot help feeling at times a conflict between his obligations to the leader and the highly personal satisfactions and freedoms he seeks in mountaineering.

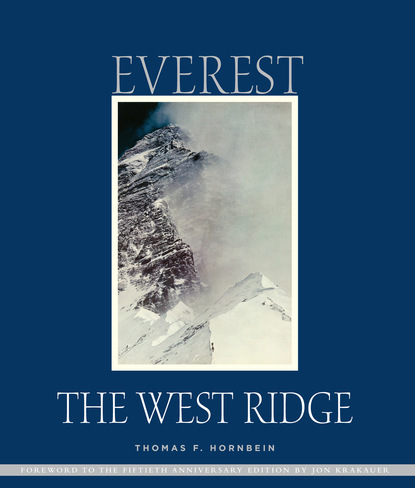

The ascent of the West Ridge and with it the traverse of Everest constitute one of the most astonishing feats in Himalayan mountaineering history. The meeting near the summit of two successful teams from opposite sides of the mountain, and their survival of a bivouac at 28,000 feet without oxygen, shelter, or food, added both intentional and unintentional embellishments to an already unique feat. Tom Hornbein has given us a stirring account of this great episode in Himalayan climbing. Everest can be an overwhelming experience that is more complex and deeply felt than simply the exposure for several months to discomfort, exhausting effort, uncertainty, and awesome scenery. The ascent of the West Ridge as seen through the eyes and mind of Hornbein brings clearly into focus the human as well as the physical struggle that is a part of climbing a great peak. In his intensely personal story, Hornbein shows a subtle insight into the feelings and impressions, the hopes and frustrations of those who would climb Everest. Each responds differently to the experience; but the country, the mountain, and the intense struggle leave deep, lasting marks—some that are scars hard to live with, and some that a man would never wish to lose.

THE 1963 AMERICAN MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION TEAM

Allen (Al) C. Auten: 36, Denver, Colorado; Assistant Editor of Design News; Responsible for Expedition radio communications.

Barry (Barrel) C. Bishop: 31, Washington, D.C.; Photographer, National Geographic Society; Expedition still photographer.

John (Jake) E. Breitenbach: 27, Jackson, Wyoming; Mountain guide and part owner of mountaineering and ski equipment store, Grand Tetons.

James Barry Corbet: 26, Jackson, Wyoming; Mountain guide, ski instructor, and part owner of mountaineering and ski equipment store, Grand Tetons.

David (Dave) L. Dingman, M.D.: 26, Baltimore, Maryland; Resident in surgery; Second medical officer of Expedition.

Daniel (Dan) E. Doody: 29, North Granford, Connecticut; Photographer by profession and for Expedition.

Norman G. Dyhrenfurth: 44, Santa Monica, California; Motion picture photographer and director; Expedition organizer, leader, and film producer.

Richard (Dick) M. Emerson, Ph.D.: 38, Cincinnati, Ohio; Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Cincinnati; Expedition logistical planner and head of sociological study on motivation.

Thomas (Tom) F. Hornbein, M.D.: 32, San Diego, California; Physician; Responsible for Expedition oxygen equipment and planning.

Luther (Lute) G. Jerstad: 26, Eugene, Oregon; Speech instructor, University of Oregon, and mountain guide, Mount Rainier.

James (Jim) Lester, Ph.D.: 35, Berkeley, California; Clinical psychologist; Studied pyschological aspects of stress during Expedition.

Maynard M. Miller, Ph.D.: 41, East Lansing, Michigan; Associate Professor of geology (glaciology, etc.), Michigan State University; Research in glaciology and geomorphology of the Everest region.

Richard (Dick) Pownall: 35, Denver, Colorado; High school physical education instructor and ski instructor; Expedition food planner.

Barry (Bear, Balu) W. Prather: 23, Ellensburg, Washington; Aeronautics engineer; Assistant to Maynard Miller in geological research.

Gilbert (Gil) Roberts, M.D.: 28, Berkeley, California; Physician; Responsible for medical planning and problems of Expedition.

James (Jimmy) Owen M. Roberts: 45, Kathmandu, Nepal; Lt. Colonel (retired), British Army; Responsible for Expedition transport and porter and Sherpa planning.

William (Will) E. Siri: 44, Richmond, California; Medical physicist; Deputy leader of Expedition in charge of scientific programme and conduction of physiological research on altitude acclimatization.

James (Jim) Ramsey Ullman: 55, Boston, Massachusetts; Writer; Official chronicler of Expedition as author of Americans on Everest.

William (Willi) F. Unsoeld, Ph.D.: 36, Corvallis, Oregon; Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy and Religion, Oregon State University, on leave as deputy Peace Corps representative in Nepal; Climbing leader.

James (Jim) W. Whittaker: 34, Redmond, Washington; Manager of mountaineering equipment store, Seattle, Washington; Responsible for Expedition equipment planning.

Nine hundred and nine porters en route (Photo by Norman G. Dyhrenfurth)

|

|

[I]f you cannot understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself upward and forever upward, then you won’t see why we

|