for me!”’13

Mannock was full of such contradictions, mixing vindictiveness with bouts of remorse. He seemed to genuinely enjoy air fighting, writing about it unabashedly as ‘fun’ and ‘sport’ in the manner of the day. But he also worried constantly that he was going to crack up. Towards the end he became convinced his death would be a fiery one. It was a common sight to see an aeroplane plunging earthwards, trailing an oily wake of smoke. Fifty-five of eighty machines shot down by Richthofen were registered as gebrannt (burned). On most aircraft the fuel tank was fitted in the nose, close to the engine. In the event of fire the backwash from the propeller blew the flames into the pilot seated behind. Once an aircraft was alight there was no escape. Efficient parachutes existed but pilots were not allowed to have them. The staff view was that possession of a parachute might weaken a pilot’s nerve when in difficulties so that he abandoned his valuable aeroplane before he had to. Anyway, one general reasoned, aeroplanes went down so swiftly there was really no time to jump.14

Mannock carried a revolver in the cockpit ‘to finish myself as soon as I see the first sign of flames’.15 The sight of his victims catching fire upset him – ‘a horrible sight and made me feel sick’, he confided to his diary after shooting down a BFW biplane on 5 September. But he referred to the victory in the mess as ‘my first flamerino’.16 ‘Flamerinoes’ became an obsession. One day after shooting down his fourth German in twenty-four hours he arrived back in high spirits. ‘He bounced into the mess shouting: “All tickets please! Please pass right down the car. Flamerinoes – four! Sizzle-sizzle wonk!”’17 It seemed to be a case of making light of that which he most feared. In London on leave in June 1918 he fell sick with influenza and spent several days in bed in the RFC club, unable to sleep because of the nightmares of burning aircraft that swamped in every time he closed his eyes. He visited friends in Northamptonshire. When he talked about his experiences he subsided into tears and said he wanted to die.

He returned to France as commander of 85 Squadron. On the evening of July 25 he bumped into a friend from 74 Squadron, Lieutenant Ira Jones, who asked him how he was feeling. ‘I don’t feel I shall last much longer, Taffy old lad,’ he replied. ‘If I’m killed I shall be in good company. You watch yourself. Don’t go following any Huns too low or you’ll join the sizzle brigade with me.’18

The following day he set off at dawn with a novice pilot, Lieutenant Donald Inglis, who had yet to shoot anything down, to show him how it was done. They ran into a two-seater over the German lines. Mannock began shooting, apparently killing the observer, and left the coup de grâce for his pupil, who set it on fire. Instead of climbing away as his own rules demanded, Mannock turned back over the burning aircraft, flying at only 200 feet. Inglis ‘saw a flame come out of the right hand side of his machine after which he apparently went down out of control. I went into a spiral down to fifty feet and saw the machine go straight into the ground and burn.’19

Mannock’s self-prophecy had been fulfilled. The bullets that brought him down appear to have come from the ground, a danger he had constantly warned against. He was credited with destroying seventy-four German aircraft by the time he died, nearly reaching the eighty victims recorded by his German opposite number, Richthofen.

Where Mannock and Ball manifested in their own separate ways certain facets of Britishness, Manfred von Richthofen was, to the point of caricature, a paradigm of Prussian maleness. He explained himself with jovial arrogance in an autobiography, The Red Air Fighter, which appeared in 1917. The von Richthofens were aristocrats, though not particularly martial ones. Manfred joined the 1st Regiment of Uhlans after cadet school and was twenty-two when the war broke out. Stationed on a quiet sector of the Western Front, he got bored and applied to join the flying service. After a mere fortnight’s training he was sent to Russia, flying as an observer. By March 1916 he had qualified as a pilot and began operating over Verdun before being transferred back to Russia, where, he confessed, ‘It gave me tremendous pleasure bombing those fellows from above’.20

Richthofen impressed Boelcke, who was on a visit to the Eastern Front looking for candidates for the new Jasta fighter units, and brought him back to the West. On 17 September 1916 he claimed his first English victim, flying in ‘a large machine painted in dark colours. Apparently he was no beginner, for he knew exactly that his last hour had arrived at the moment I got at the back of him.’ Richthofen was ‘animated by a single thought: “the man in front of me must come down whatever happens”.

At last a favourable moment arrived. My opponent had apparently lost sight of me. Instead of twisting and turning he flew straight along. In a fraction of a second I was at his back with my excellent machine. I gave a short burst with my machine-gun. I had gone so close that I was afraid I might dash into the Englishman. Suddenly I nearly yelled with joy, for the propeller of the enemy machine had stopped turning. Hurrah! I had shot his engine to pieces.’

He had also mortally wounded the two occupants. Richthofen ‘honoured the fallen enemy by placing a stone on his beautiful grave’.21

So Richthofen’s memoir continues, like the reminiscences of some grotesque big-game hunter, constantly noting his score, always on the lookout for opportunities to increase the bag. He was a ‘sportsman’ by nature rather than a ‘butcher’. ‘When I have shot down an Englishman, my hunting passion is satisfied for a quarter of an hour,’ he wrote. ‘Therefore I do not succeed in shooting two Englishmen in succession. If one of them comes down I have the feeling of complete satisfaction. Only much later have I overcome my instinct and have become a butcher.’

As a sportsman he was keen on trophies and the mess of his ‘Flying Circus’ was hung with the debris of his victims’ aircraft. It was a habit he shared with Mannock, another inveterate crash-site scavenger. In keeping with the hunter’s philosophy, he admired his prey and had strong ideas about what quarry was worthy of him. Between the ‘French tricksters’ and ‘those daring fellows, the English’, he preferred the English, though he believed that frequently what the latter took to be bravery ‘can only be described as stupidity’. Richthofen, of course, subscribed to the courtly view of air fighting – ‘the last vestige of knightly individual combat’. But he was sensible about how it should be practised. ‘The great thing in air fighting is that the decisive factor does not lie in trick flying but solely in the personal ability and energy of the aviator. A flying man may be able to loop and do all the tricks imaginable and yet he may not succeed in shooting down a single enemy. In my opinion, the aggressive spirit is everything.’22 It was an observation that was to prove equally valid when the two sides met again in the air twenty-three years later.

Richthofen’s caution meant that in a long fighting career he sustained only one injury before the end. It came on 21 April 1918 when his red Fokker triplane crashed into a beet field at Vaux-sur-Somme. As with Mannock and Ball, the exact circumstances of his death are confused. The credit for it was contested. Captain Roy Brown of 209 Squadron plausibly claimed to have been shooting at Richthofen when he went in. So, too, did an Australian machine-gun battery in the vicinity. The body was removed from the wreckage and taken to Poulainville airfield fifteen kilometres away. Richthofen was laid out in a hangar on a strip of corrugated metal, staring upwards, in unconscious imitation of the effigy of a medieval knight. In the night soldiers and airmen came in and rifled his pockets for souvenirs.

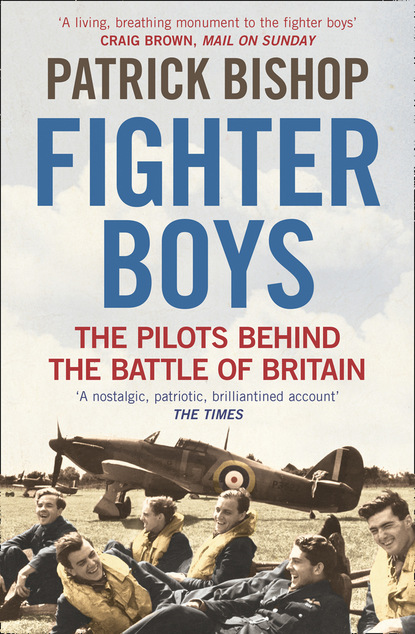

The notion of ‘aces’ placed Richthofen, Mannock, Ball and perhaps a dozen others at the pinnacle of their weird profession. Beneath them were thousands of other aviators who, though mostly anonymous, none the less regarded themselves as special. The faces that look back from the old RFC photographs are bold and open. The men have modern looks and modern smiles. Unlike the army types, whose stilted sepia portraits require an effort of imagination to bring to life, you can visualize the flesh and blood. The images pulse with confidence.

Unorthodox, even louche, though the pilots seemed to the military establishment, the ethos of the RFC was public school. Cecil Lewis, on applying to join, was interviewed by a staff officer, Lord Hugh Cecil.

‘So you were at Oundle?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Under the great