the Moon, with his torch inverted downwards, while the other behind lifts his torch upwards toward the Sun. This flow of light or energy through the Tauroctony indicates a cosmic axis or a gateway to another universe.

In the Vedic Rig Veda, Soma is a bellowing red bull8 associated with Agni, the god of fire (cognate with English “ignite”). Agni was manifested as fire, lightning, and the Sun, with the lightning bolt as the pathway uniting the solar and terrestrial fires, and also was seen as the generating source of the mushroom. Mithras is also part of this complex. In the Rig Veda, he “was pleased by Soma.”9 In the Persian Avesta, haoma is offered to him.10 Those ancient associations persisted. Thus the ninth or tenth-century medieval Armenian epic David of Sasun preserves Mithraic themes and contains many references to haoma. A most revealing example is the hero David, son of Mher, who actually eats mushrooms and becomes disoriented.11 Armenia was the ancient Parthia, whose Roman-sponsored king Tiridates initiated the Emperor Nero.

Another mushroom-like attribute of Mithras in the Avesta is his thousand ears and ten thousand eyes.12 Similarly in the Rig Veda, Soma sees with one thousand eyes.13 Multiple eyes or other sense organs make each a separate entity and indicate altered perception. They are the equivalent of the metaphor of the “disembodied eye” for visionary experience.14 A similar theme occurs in Greek mythology with the multiple eyes that are the distinctive epithet of the cowherd Argos as the “all-seeing” Panoptes.15 The white speckled cap and raiment of Mithras both depict the multiplicity of these “eyes” and the red cap of the entheogenic mushroom. His repeated epithet as the lord of the cattle pastures, moreover, can only be describing him as the bull itself. Mithras and the bull he slaughters are one entity, and Mithras is offering himself up as sacrifice.

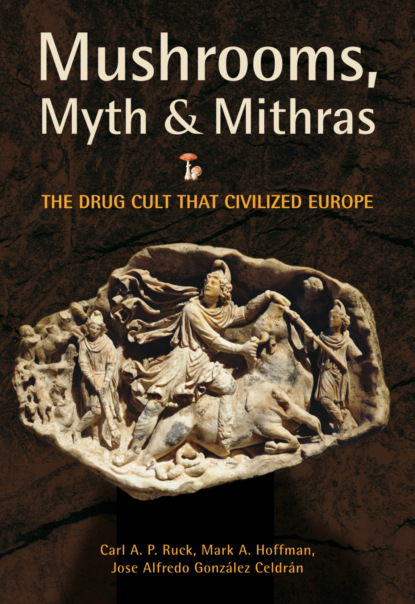

It should be remembered that there was no public display of Mithraic art. It was viewed only within the ritual space of the Mithraeum chambers and the secret meaning or interpretation of the depictions would have formed an essential part in the indoctrination of initiates. In fact, some Mithraea included additional subterranean rooms that apparently functioned as a schoolhouse.

The Mithraic bull was no ordinary bull, it was the Cosmic Bull. Its flesh and blood was not beef, but the main item of the Mithraic Eucharist, the equivalent of the Christian transubstantiated Body and Blood of Christ. Ingesting it made the initiate one with the living diety. The sacrificed bull represents the harvested plant-god Soma-haoma16 The bull is the secret society’s encrypted metaphor for their consciousness-altering Eucharist.

Cap of the Covenant

For its practicioners, Mithras was the personification of a cosmic alliance, like the Biblical Covenant and Testament, the terms of accord between the human and the divine. He was named in Sanskrit as “friend” or “treaty alliance.” In Persian, his name translates as “contract.” The earliest occurrence of the god’s name is as Mitra in a Hittite document from the fourteenth century BCE, where he is invoked to endorse a treaty.17

He was the essential intercessory or mediator between god and man—the Mesites, literally the “one who is in the middle,” and hence “joins opposites,” a function also claimed for Christ. Like the alliance of Prometheus with the Olympians in Greek mythology, the role of Mithras is the essential element in the dominance of the One God.

There is one god, one also the mediator of god and man, the man Christ Jesus (mesites theou kai anthropou).

—Paul, First Epistle to Timothy, 2.5

As the “joiner,” the god’s name actually denotes his special cap. It is the Greek mitra, a band of cloth often wrapped as a turban. As the headdress of bishops and abbots it did not achieve its present form of the stiff, joined, double front and back peaked pieces until after the eleventh century,18 although this design probably perpetuates the original meaning of Mithras as the “joiner.” The miter box, which produces the joining for cabinetry, is probably similarly derived, and the root occurs in German mit and English with. The Jewish high priest wore a similar crimson linen turban, in accordance with the Lord’s commandment to Moses, as a sign of a prophet and divine power.19 It bore a plate of pure gold, engraved with the declaration “Consecrated to Yahweh.” The design of such headdresses is symbolic of what empowers the official who wears it; hence it is similar to the ornamentation of thrones.20 Ultimately, such empowerment derives from access to the spiritual realm via the ritual use of sacraments.

In such rites, the god was thought to confer sovereignty, wisdom, and worthiness upon the kings in order that they fulfill their central role as divinely mandated. Often the sovereigns assumed the god’s name, as for example with the six kings of Pontus called Mithridates, or “Given by Mithras.”

The sixth, Eupator Dionysus, known as the Great, (120–63 BCE) lent his name to the mithradatum, an herbal concoction that is an antidote to poisons, supposedly the dog’s-tooth violet, Erythronium dens canis (or perhaps the garlic germander, Teucrium Scordium). Of most importance to this tradition is the fact that it suggests the involvement of Mithraism with pharmacological experimentation. The term “mithradatum” has come to designate the practice of building resistance to poisons by taking small and increasingly larger doses of the same substance.

The most ancient meaning of the Mithraic turban-headdress is that it is a “binding” (from the root mei-, or mi-, “to bind”), a mark of “friendship,” from “to be kindly,” deriving originally from the basic root “to place“ in the sense of assembling, marshalling, and hence inspiring.21

Whether it is the winding of the headbands in a turban or the contemporary mitre of bishops (which replaced an earlier red beret cap), the headdress signifies sacred union. In the case of Mithras, it was his defining attribute, and it took the form that strongly suggests the enthoegenic mushroom—a red, white-speckled Phrygian cap. (See color figures 3, 4, and 5, p. 98.) For the initiated, the cap symbolizes their living god and the entheogen of the Covenant that binds them to the unseen transcendant realms and ultimately leads them into Cosmic Battle. Others also wore the cap in antiquity, and it often had similar connotations of a mushroom sacrament.22

The Phrygian cap, a common artistic motif.

As the bonnet rouge or liberty cap, the Phrygian cap was adopted by the extremists in the French Revolution and nurtured by secret societies like the Freemasons, where some of their most prominent members were still aware of its mushroom identity.23 It even occurs as the red cap on the stipe of a sword, the Mithraic Sword of the Accord, in the great seal of the United States Army.24

Rapture

Just as Mithras was the friend and ally of the Lord of Light, each initiate acquired him as the guide for his own ascent to the rim of the universe, to stand entranced in the presence of the living signs of the zodiac in the Empyrean. The Classical description of such a journey occurs in Cicero’s “Dream of Scipio,” his Stoic substitute for Plato’s eschatological myth of Er in the Republic.

And as I looked on every side I saw other things transcendently glorious and wonderful. There were stars which we never see from here below, and all the stars were vast far beyond what we have ever imagined. The earth itself indeed looked to me so small as to make me ashamed of our Empire, which was a mere point on its surface.

—Cicero, “Dream of Scipio”

The most advanced level of Mithraic initiation was experienced as a liberating spiritual rebirth.

Born at dawn on this twelfth day before the first of December. (Natus prima luce duobus Augg(ustis) co(n)s(ulibus) Severo et Anton(ino) XII k(alendas) Decem(bres) dies Saturni luna XVIII.)

—Graffito,