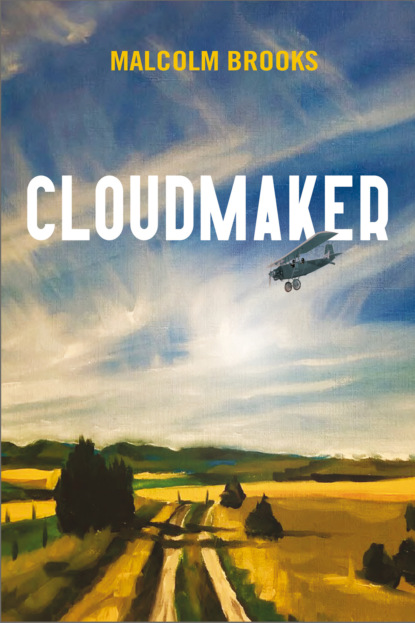

Huck was taller and he had no idea what to say to her, but for some reason it rankled that she could so much as name a de Havilland Gipsy.

“Shoot, everyone knows what that is. It’s a common ship.”

“Have you actually seen one?”

He felt the flush in his face. “Just pictures.”

“Well. You did an especially good job, then.”

“Thank you.”

They trudged a little farther.

He caved. “Have you seen one?”

“I have. A friend of mine owns one. Or a . . . friend of a friend, anyway.”

Huck knew people were looking at them as they walked along, from across the street and also from behind them after they’d nodded and helloed in passing, and he knew they weren’t looking because of the story in the Billings paper this morning. His cousin had a look to her. In a word, expensive.

She said, “I heard about the glider.”

That heat around his collar. “What exactly?”

“Oh. Not anything to speak of. I asked your dad if you’d been up, and he said you had. In a glider you’d built yourself.”

He’d expected Mother as the source, not Pop. “Yeah, I almost crashed it into the mercantile back there. The New Deal. Actually I sort of did crash it.”

“He didn’t mention that. Do you still have it? I’d love to see it. Not sure if your dad told you, but I’ve had some flying lessons myself.”

Even after nearly two hours at church and the duration of this walk, he could barely bring himself to look at her. “Actually I burned it.”

“I’m sorry?”

“I burned it.”

“Oh.” She wore a short-waisted baby-blue jacket with two rows of brass buttons above a fairly snug skirt. A darker blue beret cocked at a backward angle on her head, similar to what Shirley Temple sometimes wore. She looked like springtime rising, but nothing at all like Shirley Temple. “Why did you do that?”

He shrugged. “Didn’t work right.” Out of the corner of his eye he thought he saw her smile.

They turned the corner onto First and walked down the street in the warm air, the maples and elms already out of bud and showing new electric leaves. Early in the year to fill out so fully, though most of the snow had already blown out of the high country with the spring melt. No real rain yet to speak of. A full block from the shop Huck spotted the panel truck, backed up to the open slider door. A Stude, five or six years old. When they drew closer, he made out stenciling on the side, the legend yakima mckee blacksmith-machinist-fabricator. Hand-painted, though skillfully done.

The man himself slouched against the workbench inside the shop, perilously close to the fabrication bay. He held a folded newspaper in one hand, a bottle down against his leg in the other. He looked up and took in Annelise. “Hey, cowgirl. Want a beer?”

“McGee, I take it,” said Huck.

“I’d love one,” said Annelise. She stepped into the shop and crossed the floor toward the bench.

He reached behind for a fresh bottle. “McKee, with a K,” he said to Huck. “Highland clan. McGees are Lowland.” He set the paper down, grabbed a cold chisel off the bench and popped the cap. He handed the beer to Annelise, but he looked now at Huck. He tapped the newspaper. “Reckon you’d be the local hero. Heck of a write-up this morning.”

It was true. Pastor White had preached half a sermon on the events of the previous days, with a copy of the same morning paper for effect. He called Huck and Raleigh heroes, pointed to their God-given industriousness and tenacity and plain Christian courage to do right. Huck had sat there feeling like an idiot in a spotlight the entire time, the Lindbergh watch fairly burning in his pocket.

Annelise pulled on her beer. “I think he autographed twenty papers after church.”

He’d managed to scan a good bit of the article in the process. He and Raleigh came off like characters in a boys’ adventure novel, under the banner young sleuths stage daring recovery of gunshot baddie!

Although the both of them had glossed right over the most dangerous parts of the escapade, the newspaper managed to make the whole thing sound pretty sensational anyway. Raleigh, as usual, had the take-home quotes, one of which appeared in italics beneath the main headline: “The problem with putting two and two together is sometimes you get four, and sometimes you get twenty-two.”

“They call you Huck, eh?” said McKee.

“Yeah, some people. Rolly does, that’s why it’s in the paper. He’s the one who started it, actually. On account of my last name.”

“He must be a real piece of work,” said Annelise. “That quote under the headline? It’s from a detective novel.”

“That would figure.”

He noticed something else. McKee had toted Pop’s ancient single-shot out from the office, had it lying now on the bench beside the beer. Usually the rifle hung high up on the wall in a blanket of dust, a token of what Pop called “them wild old days.” Nobody had fired it in years, or even taken it down in as long as he could recall. Now McKee had evidently cleaned and oiled it.

He’d looked back to Annelise. “So what do they call you, cowgirl?”

“I am not a cowgirl. I’m an . . . aviatrix.”

“Oh ho.” He hooked a thumb toward the fabrication bay. “So that’s your build back there, I take it?”

Not good.

Annelise frowned. “Build? Why on earth would I have to build anything?”

“Strictly the flier, then. Reckon that leaves Junior here to be the shipwright.” He winked at Huck. “Already had that last part figured out, by the way.”

“I’m the builder and the dern dang flier.” The words just popped out and now he realized he needed a change of subject, pronto. He said, “That’s Pop’s rifle.”

This worked better than expected. McKee visibly lit up, in fact seemed to forget all mention of anything else. He pivoted and set his beer down and hoisted that beast of a gun from the bench. He cranked the breech open, looked down the bore like he was looking through a railway tunnel.

“Two-and-a-half-inch Sharps, Big Fifty. Not one you run across every day. Good solid bore, too, hard living or no.” He levered the breech block again, a sound like the clank of a vault. “See how the wood’s dished out in the fore-end? That’s from riding across a saddle.” He glanced up at Huck. “A lot. How long’s he had this baby?”

Annelise cut in before Huck could answer. “Speaking of a good solid bore, let’s stop living in the past, shall we? The future awaits.” She stepped straight for the fabrication bay.

Huck found his tongue. “Wait. You can’t go in there.”

She did pause, however briefly. “The cat’s out of the bag, Houston. Or it’s about to be, if I’m guessing right. I’m on your side, believe me.” She pushed through the door.

McKee shifted the rifle to one hand and retrieved his beer bottle with the other. “So. Pancho Barnes in there ain’t your sister, I take it.”

He knew he should follow her, but for some reason he thought to stave off the whole business, folly though it no doubt was. He looked at McKee. “Cousin. From California. I barely know her.”

McKee nodded. “Cousin. Well.” He winked and sauntered after her, rifle in hand.

“It’s a start, at least.” She was on the other side of the fuselage frame, eyeing the passenger compartment.

“Yeah, she’s getting there,” Huck