Golden Gloves boxing champion and traveled a good portion of the world, all expenses paid. It’d gotten to a level where if you don’t commit completely to training, your opponent will seriously hurt you. All the drinking, drugs, and street fighting were tearing my life apart. They began to take their toll, and I received a couple savage beatings in the ring as a result. Many professional trainers and boxers told me bluntly that I had the potential to be a very successful professional boxer. More importantly, I knew deep down I could. But there was something broken inside of me that I couldn’t quite describe, something that I was born with. That genetic flaw, combined with the partying, took boxing from me. It’s something I never got over. The run replaced boxing as my obsession, and I threw all my passion and fury into it.

CHAPTER TWO:

POSSE

2006

TRISTEZA

Got some work in construction with my family’s company when I arrived home. Things went well at work, but I ended the day with such physical exhaustion I didn’t have the energy to write. Knew if I didn’t get away I’d never complete a quality novel. My deepest dream was to become a successful novelist. Irvine insisted I had to write “every fookin’ day” for hours if I ever wanted to be a real writer. With the hard labor and my chaotic drinking and partying and the revolving door of women I kept stepping through, there just wasn’t any hope for me to write in Chicago. I saved money and figured when I got to three grand I’d drive down to New Orleans and rent an apartment in the Marigny, live simply, and write for hours every day. Then Hurricane Katrina hit. I didn’t know what to do. I contemplated my dilemma as I sat in the old Filter Café in Wicker Park, a cool, Chicago artist neighborhood at the time. A girl named Stephanie and I started talking about Mexico. She told me about a little town in Guanajuato called San Miguel de Allende. It was an old Spanish colonial town built on a large hillside, full of artists and writers and expat Americans. An idea struck me. I could go down there without speaking Spanish and still get by, maybe even learn some Spanish along the way. My money would stretch for months.

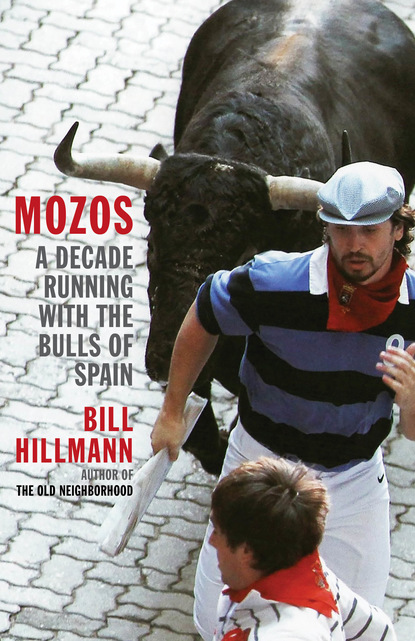

I landed in Mexico City in November, jumped in a cab, and tried to communicate “bus station” to the cabbie. He drove me to a subway station at the other side of the airport and charged me twenty bucks. I jumped on the subway and found the bus station. I paid thirty bucks for a luxury bus to San Miguel de Allende. The sun set as we slowly swayed through the mountainous region of Guanajuato. In the darkness we rounded a hill and the brightly lit city spilled into view. It splayed up a long sloping hillside glowing deep yellow. Numerous cathedral spires launched up to the sky, a big castle hung to the side. I gawked, and instantly knew I’d found a special place in the world. Rented a room at a cheap hotel and I went out that night, wandering up the cobblestone streets in the unbelievably beautiful ancient pueblo. San Miguel was the town where many believe Jack Kerouac finished On the Road and was the place Neal Cassady walked away from when counting rail ties to the nearby town of León when he died of a sudden aneurism. I knew nothing of this then but the town enraptured me. An American dance instructor helped me find a $200 two-bedroom apartment a quarter mile from the main Jardin in the town center, where elderly Americans fed pigeons in the morning light. The scent of incredibly good cheap food enticed me everywhere I went. Beautiful women and artists swarmed down each stone street. Dozens of galleries lined every sloped avenue. The art ranged from experimental to traditional Mexican. I was intending to go into a gallery on the corner when I walked into a smaller one next door. It was dark, and as I entered I realized I’d made a mistake and was about to leave when a cute, little Mexican chick with dark-brown eyes and short hair clicked into view. I tried to apologize in Spanish and explain that I was leaving when she said “Hello” and smiled. I decided to look around. Instantly a bright-orange fireball of an image leaped off the wall at me. She explained the artist was a woman name Serafina. “Nice,” I said and looked at another painting. It was of a Spanish fighting bull. I laughed and said, “I run with the bulls in Spain.”

The girl scrutinized me and said, “Yeah, right.” I laughed and said, “No, it’s true, it’s true. This past summer.” She wouldn’t believe me. I tried to convince her. She explained that she thought bull running was stupid, and she hated bullfighting and protested the bullfights in Mexico City, her hometown.

She told me her name was A-Need. I tried to say it but couldn’t. She spelled it for me: E-N-I-D. I still couldn’t say it right, but she laughed at the way I tried. We were clearly a perfect match, so I asked her out. She hesitated but said yes.

We went out for drinks that night and I took her home with me to look at the stars from my rooftop, but she wouldn’t even give me a kiss. OK, maybe one peck on the cheek. I took her out for dinner the next night and ate the thickest, rarest filet mignon I had ever eaten, and it was only twelve bucks. I bought a bottle of wine from the restaurant, which caused quite a scene, because we didn’t exactly look like a couple that could afford it. Then we walked all the way up the hill to the lookout point at the top of the city. About halfway up the hill I grabbed her and pressed her against an old oak door. I kissed her full and hard and felt her give in to me and knew that she was mine or could be mine. We walked up the hill holding hands. We talked and drank on a grassy hillside between some bushes. She wanted to know about America and all the places I’d traveled and I told her everything I’d done and everywhere I’d been and she didn’t believe a word of it until I pulled out my passport. That’s when she realized my name was William, not Bill. The soft and sweet way she said William blew me away. I didn’t correct her and she called me William from then on. I brought her home with me and it went well and well into the night.

And that was the start of my time in San Miguel de Allende.

I woke each morning to the calls of roosters. Put on Tom Waits’s Mule Variations and I cooked four eggs with cheese in butter and tortillas with refried beans. I’d fix myself a thick cup of Nescafé and go up on my open roof and smoke cigarettes and watch the horses and donkeys in the walled-in ranch that bumped up against my apartment. I’d go back down and take a huge dump. Then back to the bedroom to chant. I’m a practicing Nichiren Buddhist and member of Soka Gakkai International-USA. We chant the title of the Lotus Sutra, which translates as Nam (devotion to), myoho (the mystic law), renge (simultaneity of cause and effect), kyo (sutra, the voice or teaching of a Buddha). It’s based on the principle that world peace comes through individuals satisfying their desires and finding happiness. Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo . . . As I chanted, the voices of my characters would begin to speak to one another. I’d chant until I couldn’t hold it anymore and rush to the computer to write the dialogue, and then build the scenes around that. The writing fictionalized the many tragedies of my childhood. The catharsis of writing about those things truly healed me deeply. As the book took shape I realized I was writing about my great yet flawed father, about his redemption. My goal was to write 1,000 words each day. I met that goal for forty-something days straight; sometimes I’d surpass it by a bunch. I’d finish writing by three or four in the afternoon and then go and eat. Then no matter how we’d left it the night before, I’d find myself walking toward the gallery to be with Enid. Even if I was so mad at her and didn’t want anything to do with her, I walked to her, my white snakeskin cowboy boots clicking on the stone sidewalk, and she’d be there and I’d help her close up shop and take her out for dinner and we’d walk the town and dance and drink and go home and she’d read my writing from that day and I’d listen to her laugh at the jokes in the dialogue and then we’d fuck hard into the night with her screaming so loud that I knew all my neighbors hated me. Enid helped transform my life into a rambling machine.

It went like that for over a month until I got scared of the feeling that snuck up into my heart each time I made that walk to the gallery. A feeling I thought I’d never feel again after the intense loves in my past. She was also afraid of what was happening and confessed that she had a boy back home in Mexico City who she was in love with. He didn’t want her, but she felt I should know she still loved him.

That stung but also gave me liberty. I went out the next night without her and met a crazy white lady in a bar called La Cucaracha. She was a raunchy ex-beauty queen from Georgia who’d married a Mexican matador, though he’d passed away leaving her a thirty-five-year-old widow. Everyone in town lusted after