up to Graeme the afternoon of the sixth of July outside of The Harp bar on St. Nicholas. He staggered drunk from the Chupinazo and didn’t recognize me. He kept asking if I was a punter. I didn’t know what the fuck he was talking about. Exhausted from the long trip I almost told him “go fuck yourself” and walked off, but eventually they handed me a drink and the job of bringing punters, tourists staying with the Posse, up to their rooms above the bar.

The Posse consisted of several dozen workers from all over the English-speaking world. Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, Irish, Scots, English, and of course a few Americans; most were in their early twenties. I found an instant kindred spirit with a forty-something American from New Jersey named Gary Masi. Gary was an ex-New Jersey cop. He was big and athletic and a sick fucker. He reminded me of my football buddies. It was Gary’s and my job to settle any disputes with punters, assess and fix any damage they caused the several dozen apartments throughout the old section of town, and to kick out any punters who’d overstayed their booking. We played good cop, bad cop, and I was always the bad cop. Each morning after the run we went back to the restaurant above The Harp and ate a free breakfast: either eggs with bacon or Rabo de Toro, fighting-bull tail stew, butchered and bought straight from the Plaza de Toros. It’s a thick, spicy concoction, wholesome and hearty. Eating Rabo de Toro gave me this sense of completion: the hunt, the kill, and the feast. I ate Rabo de Toro every morning and drank red wine. After that, Gary and I’d take a full bottle of red and drift downstairs and out into the brisk and vibrant fiesta morning with our to-do list—passing the bottle back and forth along the way. The adrenaline of the morning’s run still buzzing through us, we tried to top each other with gross-out jokes; Gary always seemed to win. It was a paradisiacal existence. I threatened any cocky Englishman who spoke out of turn with serious bodily harm while Gary explained that it was time for everyone to leave or pay for an extra day. We’d laugh and bust each other’s balls along the way.

Was sitting in the plaza one night when Galloway introduced me to an elderly woman named Frosty. She was a frail, white-haired lady in her eighties and a bull runner. Graeme would position her in between two drainpipes along Estafeta behind Bar Windsor where she’d puff on a Marlboro Red as the herd rambled past. Frosty also had a long, storied history at fiesta, where she never lit her own cigarette. I lit a bunch of Frosty’s smokes as she told me stories about her decades at fiesta.

“One morning I was there on the street smoking my cigarette when the glorious herd swept past. Suddenly a few moments later a marvelous black bull appeared. He stopped right in front of me. I just froze, thinking, good heavens Frosty, what have you gotten yourself into now? He looked at me just a few feet away and tried to figure out just exactly what I was. Then the great Spanish runner José Antonio appeared. José called to the grand animal and swooped him away up the street. I really love José; he’s a dear chap.”

José Antonio wasn’t just a heroic runner who saves frail, old grandmothers. José also happened to be deaf and mute. His brother suffered from the same disabilities. His brother also had an anger problem, but José was different. He was very kind and friendly. José is one of the greatest communicators I’ve ever encountered. He’ll give all of himself to tell a simple story, using body language and objects and even writing words when needed. He is an incredibly giving friend as well. He runs the curve. To run with bulls is incredibly difficult, but to do it without the use of a fundamental sense like hearing raises the danger to outrageous heights. But the fact that José Antonio stands in the near center of the curve and waits for the animals to hit the wall before running just shows you the type of phenomenal, raw courage that churns in this man’s heart.

This time, I did plenty of research on the run in the leadup to Pamplona. I found an interesting article in the New York Times by a New York bar owner named Joe Distler. A Spanish newspaper recognized Distler as one of the five greatest runners of a twenty-year period. I’d met Distler briefly the year before and asked him a few questions. He was one of the nicer guys, with his spiked gray hair, big smile, and peppy Brooklyn accent.

Distler was a successful businessman when he read about the great American bull runner Matt Carney. At age twenty-two, Distler set out to travel to Pamplona and run with Carney.

“On my first run I ran into the arena way ahead of the herd. The Spanish taunt runners who do this and mockingly call them valientes (brave ones). I ran to the wall and jumped it, and when the herd entered the arena, the sight of those incredible bulls scared me so much that I pissed my pants. I was hitchhiking my way out of town when I stopped. I realized if the run had had such a powerful effect on me, that there must be something important back there on the street. I went back and followed Carney the next day. Later Carney became my maestro. The run was different back then. There was only a handful of runners on the street. It was wide open. It wasn’t until television and later ESPN came that the thousands of runners poured in from all over the world.”

Distler became a legend to the Pamplonicos by running on the horns of bulls for over forty years. He had the grace of a ballet dancer and a magical fluidity and speed to find his way into the pack. That, combined with his raw courage, luck, and fate, allowed him to become just the second American in history to run as the very best Spanish runners do. Matt Carney and Joe Distler are the only two foreigners to ever truly become one of them, one of the greatest runners to ever run an encierro. Distler is also known as the Iron Man of Pamplona because he didn’t miss a single run at Pamplona in all that time. A bull gored him in the nineties and dislocated his hip, which doctors eventually replaced. This along with age forced him to find a new way to continue to get close to the animals.

The article outlined an old-fashioned approach to running the curve. Chema Esparza, one of Joe’s Spanish maestros, taught it to him. The technique is to stand in a doorway just before the curve along the outer wall of the bend. Then you wait until the herd passes and crashes into the blind turn. Just as this occurs, with split-second timing you dash into a sprint and cut along the inside of the curve. As the animals rise you sprint in front of them and lead them up Estafeta Street.

After experiencing the panic and chaos the year before, I realized I needed a plan. Distler’s plan was the cleanest I’d heard yet, and I jumped at the chance to run with Joe and the others at the curve. I hadn’t brought any running shoes. I was going to run in my white snakeskin cowboy boots.

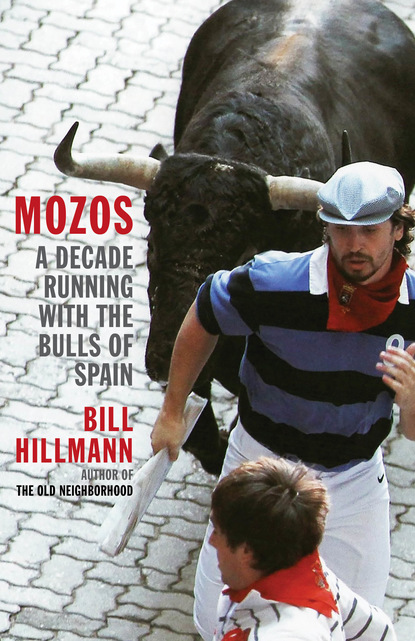

Before the third morning of runs I shook Joe’s hand and said suerte and he replied igualmente. But I had no idea what it meant and fixated on it, hoping I hadn’t pissed him off. I couldn’t see much along Mercaderes as the bulls rushed down the slow slope. Then they rocketed into view like a careening black mountain range. The exiting runner pushed us all against the wall. The bulls and steers slipped and slid on their hooves as they tried to halt and make the turn. As the last animal’s hindquarters slid past, several runners surged forward fast and cut hard along the inside of the curve. I followed. The animals slowed and slammed into the wall as I accelerated and breathed in the rank stench of bull dung and adrenaline. They bellowed and cried as the bells banged and the spectators above roared. The final bulls slipped as I closed in on them, three beasts slid in unison, their mountainous backs swelled and contorted as their momentum carried them through the turn. Their hooves skated over the stones. I could have reached out and touched them, but I didn’t. Some powerful force sucked me toward them but I feared it. I pulled away as they gathered and accelerated past and up Estafeta.

The rush impacted me so strongly that I thought I’d run beside them for twenty yards, but the photos proved I was only really beside them for a moment then drifted away. Still it was my first outstanding run. I was in the herd’s space and it thrilled me. Rushed over to Photo Auma, a shop in Plaza de Castillo, and I bought a bunch of photos. I showed them to anyone willing to stop for a second and look. In the most impressive image of my run the photographer cut my body out of the shot. The only thing that remained in frame directly beside a rising bull was my white snakeskin boot. I was most proud of this image and boastfully shoved it in everyone’s face. Once again I became a jester for the serious runners. Even Frosty couldn’t help but laugh in my face and pat me on the head. Most people dismissed the photos as not me and spread the word that I was nuts.

I caught wind and got surly and stopped showing my images. Got seriously drunk and I fell