biggest possible thing still to be accomplished in Himalayan mountaineering.” During another powwow a week later, however, he cautioned, “Let’s not go overboard on the West Ridge. I am just as excited about the West Ridge as you are.… But let’s not jeopardize the South Col. Let’s not make the mistake of throwing all the power, all the oxygen, into the West Ridge, because the Col is still our guarantee of success.”

For the next two months, almost all of the team’s efforts were focused on putting an American on the summit by way of the South Col. At 5:10 PM on May 2, Hornbein and Unsoeld were taking a rest at Base Camp when the radio crackled to life. “The Big One and the Small One made the top!” announced the excited voice of Gil Roberts, calling down from a camp 4,000 feet higher on the mountain. Despite fierce winds that had blasted the upper peak, Jim Whittaker and Nawang Gombu Sherpa had reached the summit from the South Col the previous day. Hornbein and Unsoeld spontaneously threw their arms around one another in an emotional embrace, overcome with joy for Big Jim and Gombu. But Tom and Willi had another reason to be thrilled, as well: Their friends’ success had just granted Tom, Willi, and the rest of the West Ridge crew the opportunity to pursue their pipe dream.

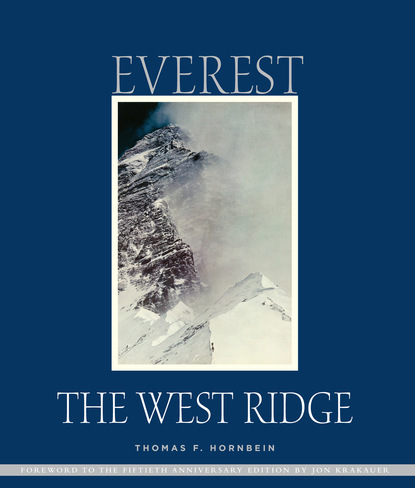

Time was running alarmingly short to establish a series of camps on the unexplored route and stock them with food, fuel, and oxygen. The West Ridgers would have only one shot at a summit attempt, and it came on May 22, just three days before the expedition was slated to pack up and head for home. At 6:50 AM, Hornbein and Unsoeld set out for the top from their highest camp—a tiny yellow tent pitched at 27,250 feet on a ledge no wider than a park bench. They had laboriously hacked the ledge, chip by frozen chip, from a steep, ice-choked gully that had been christened “Hornbein’s avalanche trap” by expedition wags, and is now officially known as the Hornbein Couloir. At 11:00 AM, 400 feet above their tent, Tom and Willi encountered the crux of the route: a sixty-foot wall of crumbly, dead-vertical limestone that blocked passage to the peak’s uppermost ramparts. With a great deal of effort and some very sketchy climbing, they ascended the cliff in two short but exceedingly technical pitches. Climbing of such difficulty had never been done at such extreme altitude. Once they were above the crux, they determined the rock was so unreliable that descending it would require them to take unacceptable risks. Their best chance of making it down alive, they concluded, would be to go up and over the summit, and then descend the other side, in keeping with their original plan.

The sun was about to disappear beneath the western horizon when Tom and Willi strode together to the apex of the planet with tears in their eyes. After twenty minutes on top they began their descent toward the South Col, following the faint tracks left by teammates Lute Jerstad and Barry Bishop, who had ascended from the Col earlier in the day, reached the summit at 3:30 PM, and headed down forty-five minutes later after seeing no sign of Tom and Willi.

Not long after starting their own descent, as the last of the daylight faded to black, Hornbein and Unsoeld arrived at the crest of the Hillary Step, the crux of the route taken by Sir Ed and Tenzing in 1953. For most of the past three decades, this nearly vertical, prowlike feature on the summit ridge has been more or less permanently rigged with fixed line, allowing modern climbers to avoid its difficulties on the upward half of the journey by ratcheting themselves up the ropes by means of mechanical ascenders, and then to securely descend the Step on the return trip by rappeling the ropes. There were no fixed lines here in 1963, however, so Tom and Willi were forced to downclimb the difficult terrain—which they managed in near darkness, without even pausing to belay one another. Indeed, they dispatched this notorious pitch so perfunctorily that Hornbein didn’t even bother to mention it when describing their descent from the summit in the penultimate chapter of this book.

Perhaps the Hillary Step failed to make much of an impression on Hornbein and Unsoeld because its difficulties paled in comparison to what followed. At 9:30 PM they caught up with Jerstad and Bishop, but more than three hours after leaving the summit, slowed by the darkness and fatigue, at that point Tom and Willi had descended only 700 feet. Although they had hoped Lute and Barry would be able to lead them down to safety, the latter were exhausted almost to the point of total collapse. Together, the four men kept struggling downward toward the South Col despite their debilitated state. As the last dregs of their bottled oxygen ran out, however, their pace grew ever slower. After midnight, unable to determine the route down in the dark, they stopped to wait for daylight on an outcrop of rock. They had no food, water, sleeping bags, or shelter. The temperature plunged to eighteen degrees below zero. Astoundingly, when the sun came up all four climbers were still alive, but they paid a high price for their night out. Bishop would lose all of his toes and the tips of two fingers to frostbite, and nine of Unsoeld’s toes had to be amputated.

When the AMEE returned from the Himalaya, the first ascent of the West Ridge was deservedly praised around the globe. As the esteemed Himalayan veteran Doug Scott wrote in the foreword to the 1980 edition of this book,

How does this West Side story fit into the sixty-year history of Everest? On close examination, it moves into a class all its own, for it was here perhaps more than on other climbs that a point of no return was reached, and a total commitment made. On other summit attempts, the climbers knew that in an emergency they had but to retrace their route of ascent back down, often down fixed ropes, to support camps. But when Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein left their top camp, they had to pass over more than 2,000 feet of unknown ground with all the accompanying little worries of where to belay or bivouac, how steep the rock steps were, what the limits of their own powers of endurance were.…

When the decision was made (or perhaps made for them?) to go for it, all thoughts and negative feelings stopped. Now that the way was clear, they tapped hidden reservoirs of energy. Now that all backward thoughts had ceased there was “no fear, no worry, no strangeness.” Now that the die was cast, they set out along the summit ridge of all Asia down into the night shadows and the terrible cold of a 28,000-foot open bivouac. Here they survived, caring not only for each other, but also for two exhausted colleagues. These were exceptional men.

A look at the Everest statistics recorded by Elizabeth Hawley, the legendary Himalayan historian, provides a sense of how difficult and dangerous the ascent by Hornbein and Unsoeld really was. Through the end of the spring 2012 climbing season, Everest had been climbed an estimated 6,204 times, and 239 people had lost their lives on its slopes, a ratio of 26:1. In comparison, only fourteen individuals have ever reached the summit of Everest via the Hornbein Couloir, yet sixteen people have perished either attempting the route or descending it after summiting via another line, a ratio of 7:8.

Hornbein was thirty-two years old when he climbed Everest half a century ago, and thirty-four when he wrote this book. He was a strong-willed, intensely focused young man at the time he ascended the West Ridge, as is readily apparent in the pages that follow. Nevertheless, readers may be surprised by how little chest-thumping they encounter in this account. Hornbein understates the risks they took and the magnitude of their accomplishment. He also writes with admirable frankness about interpersonal dynamics, and the competitive behavior that sometimes flared between climbers. He describes how some teammates lost their motivation to climb when, two days after they arrived in Base Camp, Jake Breitenbach was crushed to death beneath hundreds of tons of collapsing ice in the Khumbu Icefall—which prompts Hornbein to reflect that “it was strange how in some ways my feelings toward our undertaking were so little altered by Jake’s death.” The book offers a fascinating self-portrait of a driven, uncompromising young doctor, yet it also provides glimpses of the person Tom was in the process of becoming: the wise and compassionate friend I have come to regard with ever growing admiration over the past twenty years.

I first read Everest: The West Ridge in 1965 when I was eleven years old, and it altered the course of my life. I’ve reread it many times in the intervening decades, most recently while writing this foreword, and it still has a powerful effect on me. I was moved once again by the simple beauty of the sentences, the exquisite pacing, the admissions of self-doubt, the evocative photographs, and the book’s essential humility. During my latest reading, I was especially struck by the immense pleasure Tom took in being part of what he plainly considered to be among the grandest adventures imaginable, and how grateful he was to be able to share the experience with companions he cherished. As it turned out, not only did Hornbein play a crucial role in one of the most extraordinary