feat is one of the finest things ever written about this peculiar, hazardous, and uncommonly engaging pursuit.

Everest and its neighbors from 35,000 feet in late December light (Photo by Bill Thompson)

|

|

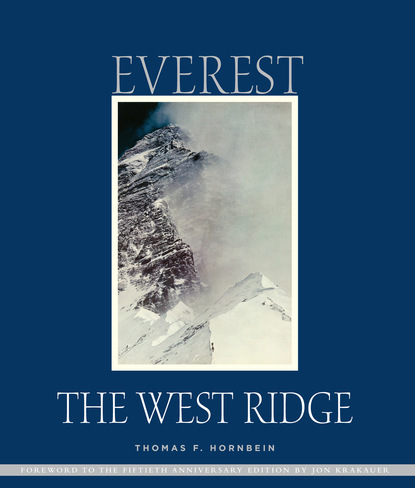

You are reminded that each man is unique. We are compounded of dust and the light of a star, Loren Eiseley says; and if you look hard at the frontispiece [now cover], Barry Bishop’s photograph of Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld approaching the West Ridge—if you keep looking at it as I have in the course of putting this book together, you will be able to see something phenomenal. They have climbed off the foreground snow by now, so you must look high, on the rock just below the summit. It isn’t too hard for an imaginative person to see there a momentary pulsing of a pinpoint of light. The light of a star. What is it that enables dust to carry it there? How could an impossibly complicated array of cells ever organize at all, much less seek out such a place to go? This inclination to inquire, this drive to go higher than need be, this innate ability to carry it off, this radiance in the heart when it happens, however brief in the infinite eternity, whether you do it, or I, or Tom and Willi, makes us grateful for the genius that man has and for the beautiful planet he has to live on. |

—DAVID BROWER

September 9, 1965

from the foreword to first edition

Early morning street sweeper (Photo by James Lester)

|

|

Flocks of birds have flown high and away; A solitary drift of cloud, too, has gone, wandering on. And I sit alone with the Ching-Ting Peak, towering beyond. We never grow tired of each other, the mountain and I. |

—LI PO

ONE LAST PREFACE

Willi Unsoeld often compared climbing Everest to the albatross in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner: “Once you’ve done it, it’s hung around your neck the rest of your career. Very difficult to shake.” In my case, it’s proved impossible. Upon returning from Nepal in 1963 part of me just wished to stuff Everest into a box with all my other climbs and get on with my life. But now, looking back from the perspective of half a century, I find that our climb and its aftermath have shaped my life in profound and mostly wondrous ways.

Among the things I’ve pondered over the past five decades is the role luck played in the events described in these pages. That I climbed the West Ridge and survived to tell this story owes more than a little to serendipity. Indeed, were it not for a fortuitous turn of events, I would not have been with my teammates when they left for Nepal in February 1963. When I was invited to become part of the team by expedition leader Norman Dyhrenfurth in 1961, I was in the U.S. Navy, stationed in San Diego. Twice I requested permission to be granted leave to join the American Mount Everest Expedition (AMEE), and on both occasions the Navy denied my request. By chance Willi and I happened to intersect in the fall of 1962 as he was heading to Nepal to take a job with the newly created Peace Corps. I mentioned my plight to him. On the following Monday, I was paged from the operating theater at the San Diego Naval Hospital to take a phone call from an admiral who informed me that I could be discharged early from the Navy to join the expedition. Before heading west across the Pacific, Willi had called his boss, Peace Corps founder Sargent Shriver, about my predicament. Shriver contacted his brother-in-law, President Kennedy, who called his Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, who sent JFK’s instruction to discharge me down the chain of command to the admiral who called me.

Luck is a two-sided coin. Two days after we arrived at Everest Base Camp, we saw its flip side when a massive serac collapsed in the Khumbu Icefall as Jake Breitenbach was climbing beneath it, killing him instantly.

Eight weeks later, in the final days of the expedition, when a furious windstorm destroyed Camp 4W on the West Ridge and almost blew us off the mountain, we figured our chance to climb the route had vanished with the wind. But a stretch of perfect weather followed, and four days later, when we rallied for one last-ditch attempt, we discovered that the gale had blown a huge accumulation of unstable snow off the mountain, purging the avalanche hazard from the steep, narrow couloir my teammates dubbed “Hornbein’s avalanche trap,” providing us with near ideal conditions.

As far as wind is concerned, we were even luckier the night after we reached the summit. A stiff, icy breeze had been blowing all day. Soon after beginning our descent, we were forced to bivouac in the open above 28,000 feet without shelter, sleeping bags, food, drink, or functional flashlights, and our oxygen tanks were empty. We would have died if the wind had not.

Yes, we were lucky. Very lucky. When I said this to a Nepalese dignitary during a reception at the Royal Palace upon our return to Kathmandu, however, the dignitary replied, “Luck is what you make of it.”

As Willi and I stood on top of Everest at sunset on May 22, 1963, I puzzled about the meaning of it all. Half a century later, I’m beginning to figure it out. The climb itself was one of many rewarding mountain adventures in my life, but it’s the aftermath of the climb that has proven to be a life-changing experience. I can no longer deny—as I tried to do for many years—that Everest has altered my life in a myriad of unimagined ways.

One example: Early in 1970 I was providing anesthesia for an urgent operation on a baby girl. Beside me at the head of the operating table stood the patient’s pediatrician, there to find out why her charge had been unexpectedly whisked away to the O.R. At a point of relative calm during the surgery she asked, “Why did you climb Mount Everest?” In order to dodge a question too often asked, I parried with, “Why’s your arm in a sling?” She explained that she was being taught to rappel. While she was getting ready to descend the short cliff, an instuctor’s ill-timed tug on the rope from below pulled her off her perch. The speedy descent that followed resulted in a broken elbow and compressed vertebrae. I suggested that she drop the course and let me teach her to climb. Now, more than four decades later, to paraphrase Li Po’s poem above, we never grow tired of each other, my partner and I.

THE EXPEDITION DID NOT END, I found, when we returned to our homes in June 1963. To my surprise, both the climb and the book I wrote about it have touched the lives of others. To inspire and to be inspired are both priceless gifts.

For the more fortunate among us, the biggest part of our lives has unfolded since 1963, and our relationships with each other have continued to evolve. I didn’t fully appreciate the strength of the bond that had grown between us until we had a reunion in the fall of 1998, prompted by Lute Jerstad’s sudden death a few months before during a trek with family and friends near Everest. His death at sixty-two reminded the rest of us that we shared something precious, and prompted our decision to have our fortieth anniversary gathering five years early.

Lute was the eighth member of our AMEE team to die. Jake Breitenbach, Dan Doody, and Willi died climbing, Barry Bishop and Barry Prather in automobile accidents, Jim Ullman and Dick Emerson of illnesses. Now, fifteen years further down the road, six more are gone—Gil Roberts, Will Siri, Jimmy Roberts, Barry Corbet, Jim Lester, and Nawang Gombu—from various illnesses. Seven of the original twenty-one are still living: Norman Dyhrenfurth, Maynard Miller, Dick Pownall, Al Auten, Jim Whittaker, Dave Dingman, and I. The oldest, Norman, our expedition leader, is ninety-four, the youngest seventy-six. Of the quartet who spent an unplanned bivouac huddled together above 28,000 feet on May 22, 1963—Jerstad, Bishop, Unsoeld, and Hornbein—I alone remain.

All this looking back and reflecting—perhaps it’s because there’s so much more behind than ahead. In my ninth decade, there is no denying the proximity of that finish line. As Gil Roberts said in his farewell